The preacher who wants to concentrate on this Sunday’s gospel reading is fortunate in not needing to desperately hunt around in their imagination for a compelling illustration to start things off. Instead it’s there in front of us – as it is every week. Yes, this is what it’s all about. A table!

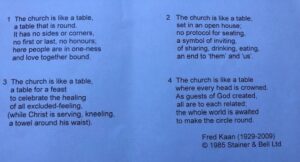

In a way, Fred Kaan’s hymn (above) has said it all, but Sunday by Sunday the table is here reminding us that shared meals and hospitality are themes that run through the gospel story. When we share bread and wine together here we remember the particular events of the night of Jesus’s betrayal, but we should realise that the meal we describe as the last supper was, as the name implies, simply a repetition of countless such gatherings. Eating and drinking together was more or less an everyday event for Jesus and his friends, and from early on in his ministry, Jesus had gained a reputation for enjoying good food and drink. And indeed right from the beginning of the story, particularly as Luke was to tell it, there had been a focus on what was to be found on the table. Mary’s Magnificat song refers to the hungry being filled with good things, while the rich are sent away empty.

Not that every gospel meal was taken round a table. The hungry were filled unexpectedly and inexplicably as they sat by the lake, spellbound by Jesus’s words and actions. And nor was every meal that Jesus enjoyed taken with the same group of friends: think of Martha and Mary in Bethany. Was Lazarus around that day too? It seems that the other disciples weren’t. And sometimes there were meals taken in more unlikely company, where the atmosphere could be distinctly frosty. Which is where we have met up with Jesus this morning.

He has been invited to the house of a leader of the Pharisees. I think that means a local leader – it’s as if you get an invitation to a meal at the manse or with one of the elders, only Jesus is not going to be as comfortable as you are expecting to be. The thing with the Pharisees is not only that they are strictly religious, but also that their understanding of what it means to be religious has very strong social implications. It’s probably fair to say that in the very varied world of religion and religions, there are still two areas of life that cause the most concern and division. One of them is sex, and the other is food. Xty has generally tended to be more obsessive about sex, as we see today as churches sadly tear themselves apart over issues of sexuality, while most other faiths display their obsessions through food, and things like dietary laws that we are so relieved not to have to follow ourselves.

The Jewish food laws of Jesus’s day could be pretty restrictive, and the mark of the law-loving Pharisee was to ensure that every commandment and every instruction was followed to the letter. Which meant that Pharisees would generally only eat with other Pharisees – they didn’t want risk being in less exacting company. And add to this the general understanding of honour and status that ran through polite society in the ancient world, and we realise that no local leader of the Pharisees is going to invite anyone to his house who is less than his social equal, or who is at least seen to be a figure of such significance that they will enhance his reputation in the community. So what on earth is going on, that Jesus should have been invited here?

I’m not sure if even Luke has the answer to that one – but there are clues at least in his introductory paragraph when he tells us that “they were watching him closely”. It is the sabbath, of course – and the verses we’ve missed out tell the story of Jesus first healing a man who has dropsy. Again, ask the question, What was he doing here? So maybe it’s all been a put-up job, and the generous invitation to the Friday night feast was just a means of catching Jesus out, and publicly condemning him as a law breaker and threat to decent religious society. But as we may find for ourselves, if we ever try to challenge Jesus and even try to catch him out, he can have a way of turning the tables.

I’m sure we need to be asking ourselves where we think we fit into this story, and I suspect Luke is thinking that we as good church people might be more like the local Pharisees than we want to admit. Probably most of us don’t think of ourselves as religious as such – that sounds kind of narrow and exclusive. But what is that brings us here? What is it that makes us comfortable at least, maybe even at times eager, to be together round this table? We kind of know that the right answer has to do with the presence of Jesus and the prompting of his spirit, but at the same time we know that we come here because (for many of us) this is what we’ve always done, and maybe this seems right to us because this is how things are in our family and among our friends, and also in a world of increasing confusion and moral uncertainties we recognise that there are standards and traditions and customs that we really value, and want to affirm and hold on to. Are we then so much different from the Pharisees sitting across from Jesus that evening?

It’s so easy to feel good about ourselves, and miss where we’re falling short. It’s so easy to be like the eagle-eyed dinner guests who are watching Jesus’s every move, as we criticise and condemn other people, while unaware of what they may think of us. It’s likely that this meal at the Pharisee’s house is quite formal, at least to the extent that there’s an official break, almost like a second course, following the Greek symposium pattern. The guests are waiting for a latter-day Plato or Socrates to start the ball rolling: surely one of the men who’ve been making polite conversation with Jesus over the first course will now take the lead? Now’s the time to criticise him publicly, and question him about his blatant sabbath-breaking and his loose attitude to the food laws. But somehow or other, it doesn’t happen: instead it’s Jesus who now takes the lead. It’s Jesus who criticises the Pharisees, not the other way round. Little did they realise it, but it was he who’d been watching them all the way along. And he now embarrasses them as he ridicules their pubic behaviour.

Yes, he’d been watching. These were the men who turned out for an occasion like this simply to polish their public image. They summed up the room as they came in: they noted where the empty seats were and they made sure they took the best for themselves. So Jesus doesn’t lecture them on their attitude to the law, but simply gives this little “what if?” story. Say you were at a really grand event, a big wedding do, and you carried on like this as you’re doing here and made straight for the top table, only to find that your host didn’t share your assessment of your social standing…. When you understand how much the world’s opinion matters to these people, you can guess that things have gone very quiet up and down the table. Where do we find our place here? Higher or lower? Who’s the host at this table, and what is he going to have to say to us?

It’s possible of course to hear this story simply as commentary on social etiquette, as if Jesus is contributing to Debrett’s handy etiquette tip of the day. If you find yourself in a socially uncomfortable situation, then keeping to the back is good advice. But I’m sure Jesus is doing more than this. For all through his ministry, whether through preaching and healing, or as on this evening through conversation round the table, Jesus is helping his hearers to understand the nature of God and the boundless quality of his love. It is God who comes to us at the table, and it is God who searches out the humble and the hungry and those who are despised by the rich and the powerful: he searches them out and he lifts them up.

Fred Kaan’s hymn suggests a table that not only has no sides or corners, but in fact has no finite dimensions. For the table-like Church has to be inclusive in every way, and if we are to follow in the way of Jesus and continue to tell his stories and demonstrate the boundless love of God, then we all know in our heart of hearts that there have to be some changes in our attitudes and in our actions. I sense Jesus watching us as keenly as we was watching his fellow guests that evening: being at table with him, whether he is host or guest, can be more than a touch uncomfortable.

Just now we are more aware than ever of just what physical hunger and empty tables may mean for more and more of our immediate neighbours. And as we look towards the winter and increasing fuel costs, we know that impossible decisions will have to be made by people who probably aren’t anywhere around our churchy tables; and I wonder, are we really aware of their needs? Have we thought what we can do through this crisis? Whether it’s practical support for food banks and kitchens, or making warm space available for everyone, or whatever is appropriate and possible in our different contexts, this is going to be a time when we have to get our ideas straight about the table and who finds a place around it here. In this country the Church clearly has lost its way; and this would-be round-table church has work to do, bringing an end to them and us.

“Invite the poor, the crippled, the lame and the blind” says Jesus, provocatively to the people who really don’t want to be mixing with the likes of them. And we can always find good reasons by looking into the deeds and hearing the advice of the trustees and the recommendations of various committees and all the rest of it – good reasons for keeping the table neat and square and adequately cornered. It’s going to be hard just now, but it’s always been hard, to act as though Jesus means just what he says. “Invite the poor, the crippled, the lame and the blind”. The best parties probably are those where there has been a bit of anxiety about the invitation list. But Jesus says, Invite them, and you will be blessed. The whole world is awaited to make the circle round.

John Durell

Preached on 28th August 2022